“Plain and Simple:” The Ideal Diet for a Child According to John Locke

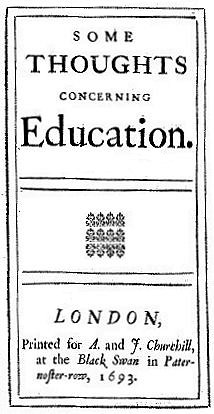

“As for [the child’s] diet, it ought to be very plain and simple,” said the philosopher and political theorist John Locke in 1693 in his Thoughts Concerning Education. Bread, bread, gruel, and barely alcoholic small beer, basically.

The Thoughts Concerning Education, most scholars agree, was the most important English-language work on education of the eighteenth century. Well-to-do French, Italian, Dutch, German and Swedish families could read it in multiple translations.

It was “the most practically significant book Locke ever wrote” according to the distinguished American historian of the American Revolution, Gordon S. Wood, writing in the New York Review of Books in 1983.

In short, there’s every reason to believe that Locke’s ideas shaped the child-rearing of the upper classes and filtered down the social scale as well.

The ideal diet for the child (or rather, boys of the upper class) occupies most of the first part of the Thoughts as I discovered last week when for reasons having nothing to do with food, I started re-reading the Thoughts Concerning Education last week. He puts it up front before he gets on to the topics generally discussed by scholars, such as virtue, reason, the nature of the mind, and the avoidance of corporal punishment.

Underlying his dietary recommendations was Locke’s belief that “the strength of the body lies chiefly in being able to endure hardships.” (He also recommended exposing children to cold).

Children should subsist largely on bread, often dry, often brown. This could be supplemented with bread-y dishes such as gruel, and accompanied by the barely alcoholic small beer that was standard for children at the time.

Very little meat, no sauces, no spices, fruit only of certain kinds and with caution, and milk (except in pottage), butter, cheese, eggs, and vegetables not even deemed worth a mention.

I have excerpted Locke’s main points below, though the whole section is worth reading on one of the free pdfs in Google Books, Hathi Trust, etc.

“Flesh should be forborne . . . at least till he is two or three years old.

Plain beef, mutton, veal, &c. without other sauce than hunger, is best . . .

Great care should be used, that he eat bread plentifully, both alone and with every thing else. . .

A Boy, Well-Born Judging by his Dress, with a Basket of Bread, ca. 1660, by the Italian painter Evaristo Baschenis

Whatever he eats that is solid, make him chew it well. . .

For breakfast and supper, milk, milk-pottage, water-gruel, flummery, and twenty other things . . . are very fit for children . . .

[Make sure] they be plain, and without much mixture, and very sparingly season’d with sugar, or rather none at all . . .

Especially all spice, and other things that may heat the blood, are

carefully to be avoided . . .

Sparing also of salt . . .

If he at any time calls for victuals between meals, use him to nothing but dry

bread. . .

His drink should be only small beer [less than 1% alcohol]. . . after he had eat a piece of bread. . .

Take great care that he seldom, if ever, taste any wine or strong drink.

Melons, peaches, most sorts of plums, and all sorts of grapes in England, I think children should be wholly kept from, as having a very tempting taste, in a very unwholesome juice . . .

Strawberries, cherries, gooseberries, or currants, when thorough ripe, I think maybe very safely allow’d them . . .

Apples and pears too, which are thorough ripe, and have been gather’d some time, I think may be safely eaten at any time, and in pretty large quantities, especially apples.

Fruits also dry’d without sugar, I think very wholesome. But sweet-meats of all kinds are to be avoided.”

I have lots of thoughts on Locke’s recommendations which I will blog about soon. In the meantime, I’d love reactions to what were undoubtedly widely influential recommendations.

If these recommendations were widely followed, it’s scarcely surprising that young rich men would break out into feasting and drinking once they were under their own control.

Oh, they were followed, believe you me.

Pretty standard advice. Compares interestingly with Rousseau’s Emile.

Agreed. Nicely laid out, though.

The most interesting thing for me is the low alcohol beer which was probably extremely nutritious and excellent for digestion…. also I would imagine that the bread of those times was with out a doubt more nutritious than what we in general call bread these days. thanks for sharing!☺

Yes to both those comments, Jason. This would have been a good diet at the time.

Would part of the drive behind such a limited diet be due to the problems of disease? I’m no historian nor health professional but I’m assuming bread would be less vulnerable to spoilage that causes illnesses than vegetables and dairy.

Milk was certainly a dangerous substance. Vegetables were highly seasonal. So, yes, disease played a role. More important was scarcity. It’s hard for those of us alive today to understand just how precarious the food supply was through most of history. If the child had wheat bread, he was one of the lucky few. Most had breads of less prestigious grains (oats, barley).

Pingback: John Locke - Sprouts - Learning Videos - Social Sciences