The Food Book Fair takes place at Brooklyn’s Wythe Hotel. The Fair will include two panels presented by the New York Academy of Medicine, Food and Empire and Cookbooks and History. For more information and for tickets, visit foodbookfair.com.

“Where’s the beef?” asked actress Clara Peller of a rival burger in a 1984 Wendy’s advertisement. Within a matter of weeks, her words had become an American catchphrase.

Curious, though, when you think about it, that Americans were so enamored of beef. Through most of history, beef was low on the hierarchy of meats. Chinese preferred pork or fish; people in the Middle East and the Mediterranean relished lamb and goat; and Indians created cuisines in which meat played a secondary role if not avoided altogether. Most people stayed away from the tough stringy meat from old work animals or worn out dairy cattle.

Northwestern Europe and its former colonies are the exceptions. For Americans, for example, not only is beef delicious, but they and others see it as a symbol of American power, particularly when combined with white bread to make a hamburger. On January 31, 1990, 5,000 people waited in the chilly Moscow dawn for the first McDonald’s in the USSR to open its doors; by nightfall, 30,000 had been served. Many commented that the opening of McDonald’s foreshadowed the fall of the USSR.

Because McDonald’s was so symptomatic of American strength, no one took it lightly, whether they liked it or not. The Economist used the price of a Big Mac to value the world’s currencies; the sociologist George Ritzer coined the term McDonaldization to mean efficiency, predictability, and mechanization. In the 1980s, the Slow Food movement took its name as it opposed the opening of a McDonald’s in Rome. In 1999, the French farmer José Bové dismantled a McDonald’s under construction in France, rallying supporters with the call McMerde (McShit).

Beef as the symbol of American power was a natural successor to beef as the symbol of British power. Beef, the flesh of the most powerful domesticated animal, its bright red color suggesting strength and masculinity, had been hallowed by the English since at least the 17th century. In song, in quips such as the “roast beef of Old England,” in clubs centered around eating steaks, and in ox roasts distributed to the poor on political occasions, beef became synonymous with Englishness. When Justus Liebig, the leading chemist of the first half of the 19th century, declared that proteins were the crucial nutrients, essential to the building and maintenance of the body, English faith in beef was confirmed.

In fact, steaks and roasts were beyond the means of most English in the 19th century. Sticky brown essence of beef provided, as hamburger offered later, an affordable alternative. Meat extract, according to Liebig, was as nutritious as beef itself. He offered to provide it neatly bottled from his factory in distant Uruguay, which extracted beef essence from cattle carcasses hitherto valuable only for their fat and hides.

Beef essence was one of the fastest growing areas of the food-processing industry in the 19thcentury, with entrepreneurs from the American meat packer Armour to the chef Escoffier investing their reputation and money in extracts.

One of the most successful companies was Bovril. Its name combined modern theories of race embodied in the bestselling novelThe Coming of the Master Race(1871) by the politician Edward Bulwer Lytton, and classical antecedents of empire. The first provided “Vril,” the name for all-penetrating energy harnessed by a subterranean race of super men, and the second “bovis,” Latin for “of the ox.” According to a series of stunning advertisements, this small jar of brown syrupy stuff strengthened men at the front, built up children bursting with health, and averted influenza, no small matter when the 1918 pandemic killed three to five percent of the world’s population.

Meat extract, like hamburgers later, depended on an infrastructure that stretched from the advertising and retailing industries, through the steamships and trains that shipped carcasses to factories and gleaming bottles of extract around the world, to vast areas of land. In 1932, Bovril ran cattle on 1.3 million acres in Argentina and 9 million acres in Canada, over ten times the acreage of the King Ranch in Texas, which claimed to be the biggest in the United States.

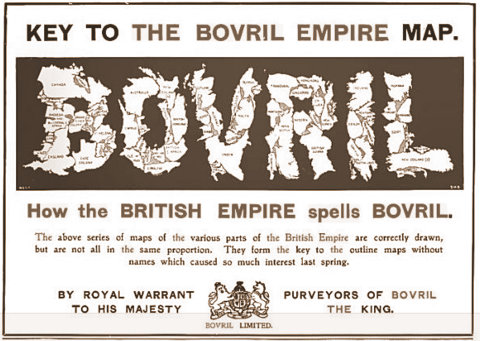

Inevitably, the power of beef came to be seen as underpinning the expanding British Empire. To mark the coronation of Edward VII, the major British weekly The Illustrated London Newsran an advertisement on February 2, 1902. Titled “How the British Empire Spells Bovril,” it illustrated “the close association of this Imperial British Nourishment with the whole of King Edward’s Dominions at Home and Beyond the Seas” by fitting the national outlines (reduced or expanded as necessary) into the letters of the word Bovril.

Today, although English soccer fans still take hot Bovril broth to games, the idea that it is nourishment for Empire builders is long gone. And even McDonald’s is not the power it was a decade ago. Consumers go instead to Chipotle, Panera, and Starbucks, which offer the promise of healthier, tastier, less mass-market foods. Is this the end of empire? Or a change of direction?

Interesting!

Have you ever heard of cowboys?

Yes. And of opening up of grasslands and refrigerated transport and meat packing plants. So if your question is, wasn’t all this the result of new sources of beef, well, yes, new sources were necessary. But so was the attitude that fresh beef was strong desirable food. And it’s the demand, not the supply end I am looking at in the 600 or 700 words I was allotted.

You might be interested to know that McDonald’s chain is struggling to stay open here in Greece, and not just because of the crisis. They were in trouble even before the current crisis. On the other hand, many new and better local hamburger places have opened. I assume that the cheap version just doesn’t go over with the Greeks, who although they now have less to spend, prefer to spend what they do have on real food. Many McDonald’s and KFC’s have closed as well as Taco Bell, Wendy’s etc. In Mediterranean countries even young people appreciate fresh unadulterated ingredients. Something for all of us – not only McDonald’s execs – to think about. Found your article interesting. Thank you. Linda Makris, Athens, Greece

Thanks for filling me in on this. There’s lots of evidence that the mood about food is changing in Greece, in the US, in much of the world. I’d put it down to a change in what real food is perceived to be, not in a change from fake/ersatz/false food to real food. If we choose the second option, it’s hard to understand why McDonald’s etc had such appeal short of resorting to consumers duped by corporations.

Interesting – meat extract also became a favorite with some of the 19th century explorers in Africa – extract, or ‘paste’ as it was sometimes called, was a great favorite/

Yes, paste (love the English choice of words) was just the thing for explorers. And Bovril ads made the most of it.